“Society grows great when men plant trees in whose shade they will never sit."

— Source unknown

I.

April 2016. I exited the metro station into the beautiful Catalan sunshine, and looking up, my eyes struggled to adjust. Against a backdrop of the deep blue sky, the towering spires of the iconic basilica stretch up towards the heavens — as do the cranes surrounding it.

This was my first glimpse of La Sagrada Familia, one of the most stunning buildings I’ve ever laid eyes on.

The cranes are there because it’s still under construction. They’re expecting to finish it some time in the 2030s. About a hundred and fifty years after they began, give or take.

Although construction began in 1882, the project hit its stride a year later, when a young Antoni Gaudí came on board as the lead architect. Gaudí infused the design with his remarkable blend of Gothic and Art Nouveua, which is what gives La Sagrada Familia its unique style of the ornate and the colourful.

Imagine Gaudí’s excitement. At the age of just 31, he had a fast-growing reputation as one of the best up-and-coming architects in the world. Then he was handpicked to be the lead architect of La Sagrada Familia? Amazing.

This was the oportunity of a lifetime. Literally. Gaudí worked on this project for nearly 40 years, until he passed away in 1926.

At the time of Gaudí’s death, La Sagrada Familia wasn’t even 25% finished. But that’s OK. Asked, about the lengthy construction timeline, the devoutly Catholic Gaudí pointed towards the heavens, and remarked, “My client isn't in any hurry.”

What sort of mentality does that take?

II.

From the world of Gothic & Art Nouveau Catholic architecture, to the self-involved world of thinking about our own careers. Most of us are not devoutly Catholic architects looking to leave a mark on history. We are people with busy careers, social lives, exercise plans, hobbies, and everything else we want to cram into our lives.

Yet, we can still learn from Gaudí.

Let’s contrast the careers of two recent university graduates.

Here’s the first:

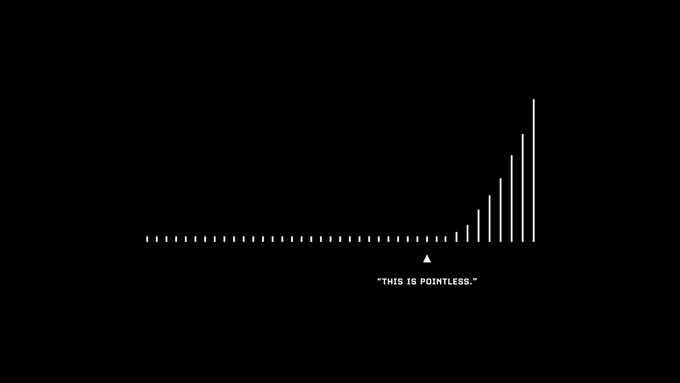

How do you think that person’s career is going to progress over the coming years?

Given the entitlement and impatience, I doubt they’ll go far. One of my favourite quotes on this is from the 1902 classic book Letters from a Self-Made Merchant to His Son:

There’s plenty of room at the top, but there’s no elevator in the building.

This person is desperately looking for an elevator, where none exists.

Contrast that with a young kid, a couple of years out of college. He’s had a few roles at various startups and media companies, none of which have quite fit him. Recently laid off, he’s pondering his next move.

He thinks, maybe I want to be a creator. Enamoured by the success of Casey Neistat, he spent several weeks shooting YouTube videos around Manhattan. Until he realises, in fact, he prefers writing rather than filming. He loves reading, writing and ideas so much that he wants to dedicate his life to it. He knows this will take time to blossom into a promising career, so he plucks up the courage to phone his parents, and says,

“Dad, I’ve got the worst plan for two years, the best plan for ten. Trust me.”

That was David Perell, seven years ago.

Fast forward to today: David has nearly 400k Twitter followers, a fantastic portfolio of writing, and a highly rated podcast. His thriving education business doesn’t publish revenue numbers, but my guess is that it’s well north of $10m.

And David still has three years to go on his original ten year plan.

That’s the value of patience. The worst plan for two years, the best plan for ten.

III.

We need to radically rethink what we mean by ‘productivity.’

In today’s world, productivity has become the holy grail of success. We want to Get Things Done. We want to hustle. We want the magic formula for maximizing output with minimal input. We want to take on everything and conquer the world.

The result? A culture of constant ‘hustle,’ where burnout, stress, and anxiety have become all too common. People push themselves to the limit in the pursuit of efficiency every waking hour of every day.

Let’s call this phenomenon ‘fast productivity.’ That’s what we should be avoiding.

In contrast, author and professor Cal Newport argues that we should instead be aiming for ‘slow productivity.’

The key question for slow productivity is this:

What if you shifted your timeframe of how you measure productivity? Rather than aiming to be as productive as possible over the next 24 hours, what if you aimed to be as productive as possible over the next 10 years?

Ten years? That’s a long time. If you were trying to be as productive as possible over a decade, you’d probably do a few things differently.

Firstly, you’d look after yourself better. You’re in this for the long haul, so you need to stay healthy and well-rested.

Secondly, you’d probably reduce the number of things you’re working on at any given time. You’ve got a decade to achieve them all, so what’s the rush? Better to do things sequentially, focusing on doing each one then moving onto the next.

Next, you’d be willing to spend time on things that won’t pay dividends for a while. It might not look like you’re accomplishing much today, but that’s OK. You know that the seeds you’re planting today will sprout in good time.

You’d take more risk: after all, a decade is a long time. You’ve got a chance to recover from almost any setback. But not too much risk: you need to avoid anything that puts you out of the game entirely. As Taleb says, “one may love risk yet be completely averse to ruin.”

And you’d probably aim for more ambitious targets too, because hey, a lot can happen in ten years.

The punchline is that, very special circumstances aside, this is how you should be thinking the whole time.

IV.

The only certainty of life is that one day, you’ll die.

Yet we also have to reconcile that with the fact that, ten years from now, you’ll probably still be alive.

How do you balance the need to think long-term, while also respecting the inevitable shortness of life?

One way to reconcile this contradiction is to take the advice of everyone’s favourite investor-philosopher, Naval Ravikant:

Impatience with actions, patience with results.

Keep moving forward. Get your head down and do the work. Rest if you need it. Look after yourself. Trust the process. Play the long game. The results will come. Maybe not today, maybe not tomorrow. But if you think in decades rather than days, does it really matter whether it’s today, tomorrow, or a year from now?

The second way to overcome this contradiction is to borrow a tactic from the New Zealand’s national rugby team, the All-Blacks.

As author James Kerr describes in his excellent book Legacy, when a player wins a spot on the All Blacks team, he is handed a photo book.

It’s a small black book, bound in fine leather, and beautiful to hold. The first page shows a jersey – that of the 1905 Originals, the team that began this long whakapapa. On the next page is another jersey, that of the 1924 Invincibles, and on the page after, another jersey, and another, and so on until the present day.

Those photos represent all the players that have come before him.

The next few pages are blank. One of those pages will belong to that player: it’s where he’ll leave his mark. The pages after that are for the players that will come after him.

The purpose of this exercise is to point out to the player that yes, he is on the team for now, and it’s his turn to wear the jersey. One day that will end, and he’ll need to pass it on to someone else.

The goal, then, is to leave the jersey in a better place. Play with heart, passion, skill, determination. Honour the work done by those who came before you, and give those who come after you something to live up to.

This is exactly what Gaudí did. He knew that completing La Sagrada Familia would be his life’s work, and then some. "All particularly grandiose churches have taken centuries to complete," he said. “Another generation will collaborate, as is always the case.”

Society grows great when men plant trees in whose shade they will never sit.

Let’s go plant some trees.